When I was a kid, I was fascinated by maps. I had a light-up globe that I’d stare at for hours before bed, memorizing all the capitals of the world while (apparently) annoying my sister — yes, I was a proper nerd. But I think it helped shape how I see the world: I tend to abstract everything as a kind of map. That habit still defines how I think today, whether it’s mapping out the space of possible symmetry-breaking mechanisms in gene regulatory networks or trying to win a game of Carcassonne. Mapping possibility spaces is really at the heart of everything I do.

When I was a kid, I was fascinated by maps. I had a light-up globe that I’d stare at for hours before bed, memorizing all the capitals of the world while (apparently) annoying my sister — yes, I was a proper nerd. But I think it helped shape how I see the world: I tend to abstract everything as a kind of map. That habit still defines how I think today, whether it’s mapping out the space of possible symmetry-breaking mechanisms in gene regulatory networks or trying to win a game of Carcassonne. Mapping possibility spaces is really at the heart of everything I do.

At its deepest level, my primary interest—like that of many other scientists—was best expressed by Schrödinger in his simple yet profound question: "What is life?" How has highly organized life, with low information content, emerged despite thermodynamics driving us toward maximal entropy?

The information-theoretic aspect of biology is what initially drew me to studying pattern formation in development. Its allure is undeniable: How does a group of identical cells become different from one another? Alan Turing’s work on morphogens—where a simple system of diffusing auto-activators and repressors can break symmetry in a seemingly counterintuitive way—captivated me and led me into the world of dynamical systems theory. Even now, I continue to ponder the question "What is life?", but always through the lens of information theory and dynamical systems.

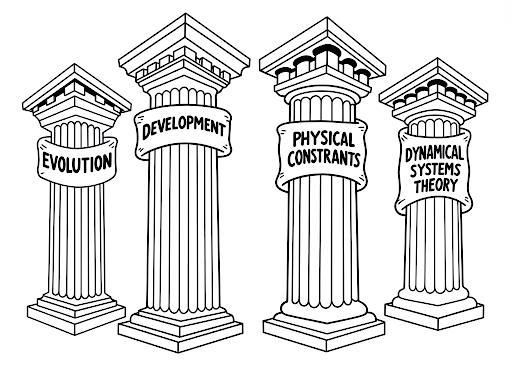

It is often said that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. However, I believe this perspective is incomplete. Personally, I extend this idea to also account for the constraints of development and physics. A fundamental difference between biology and engineering is the role of contingency in the former. As engineers, we can more easily "go back to the drawing board," discarding previous ideas and starting anew—something we often see during major technological advancements. Biology, however, lacks this luxury. Evolution must build upon what already exists, constrained by its own history. These contingencies are not merely incidental; they are essential for understanding biological systems and their evolutionary trajectories. These contingencies ARE developmental biology.

Whether evolution proceeds through neutral drift, is driven by natural selection, or is influenced by other processes, one common denominator remains: the underlying map upon which populations evolve. This map is defined by physical principles that delineate the possible from the impossible, which is precisely where dynamical systems theory and information theory become crucial. Additionally, intrinsic properties of a population—such as its size—significantly influence its evolutionary trajectory through possibility space. I have always been inspired by the foundational work of evolutionary biologists like Ernst Mayr, Stuart Kauffman, John Maynard Smith, and Sergey Gavrilets, who have played instrumental roles in shaping our understanding of these processes.

See terms of use tab.